REFRACTED REALITY

Taking the window as a motif and metaphor, Refracted Reality presents the work of ten artists and collectives whose practices frame the complexities of human nature as a vivid spectacle of truths. The works presented in this exhibition become the medium through which ideas pass and bend, portals for reflection, transition or exchange. The artists explore mediated truth, personal sovereignty, and the environmental upheavals that frame the Australian psyche. Refracted Reality seeks to create a space of shelter, inviting viewers into intimate environments and private rituals that reflect a spectrum of perspectives and alternative realities.

Hoda Afshar, Bruno Booth, Helen Britton, Max Pam, Karrabing Film Collective, Bruce and Nicole Slatter, Valerie Sparks, Angela Tiatia, James Walker and Ian Williams.

Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Perth, WA.

3 November 2020 - 10 January 2021.

Hoda Afshar, Bruno Booth, Helen Britton, Max Pam, Karrabing Film Collective, Bruce and Nicole Slatter, Valerie Sparks, Angela Tiatia, James Walker and Ian Williams.

Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Perth, WA.

3 November 2020 - 10 January 2021.

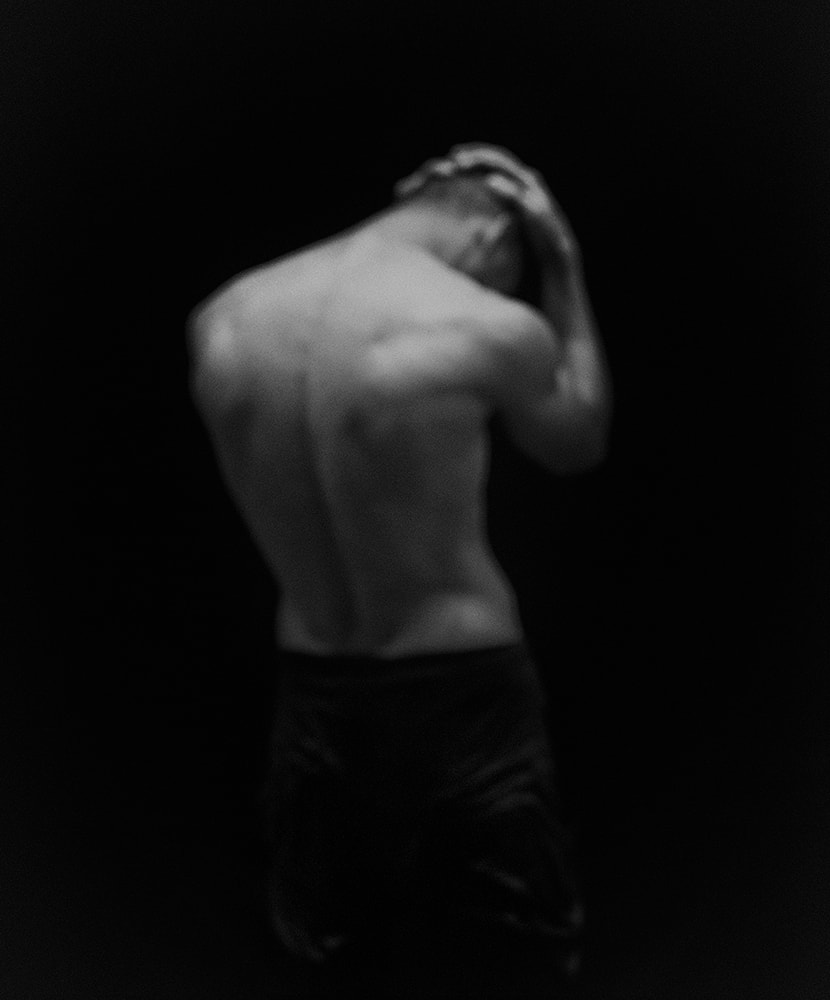

Hoda Afshar, Portrait of Aref, from the series Remain, 2018 Archival inkjet print, 100 x 83cm (left)

Hoda Afshar, Portrait of Behrouz Boochani #2, from the series Remain, 2018 Archival inkjet print, 100 x 83cm (right)

Hoda Afshar, Portrait of Behrouz Boochani #2, from the series Remain, 2018 Archival inkjet print, 100 x 83cm (right)

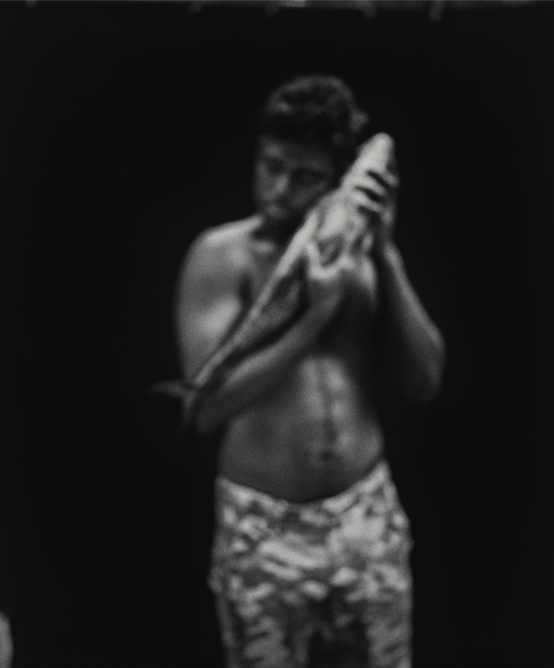

Hoda Afshar, Portrait of Ramsiyar, from the series Remain, 2018 Archival inkjet print, 100 x 83cm (left)

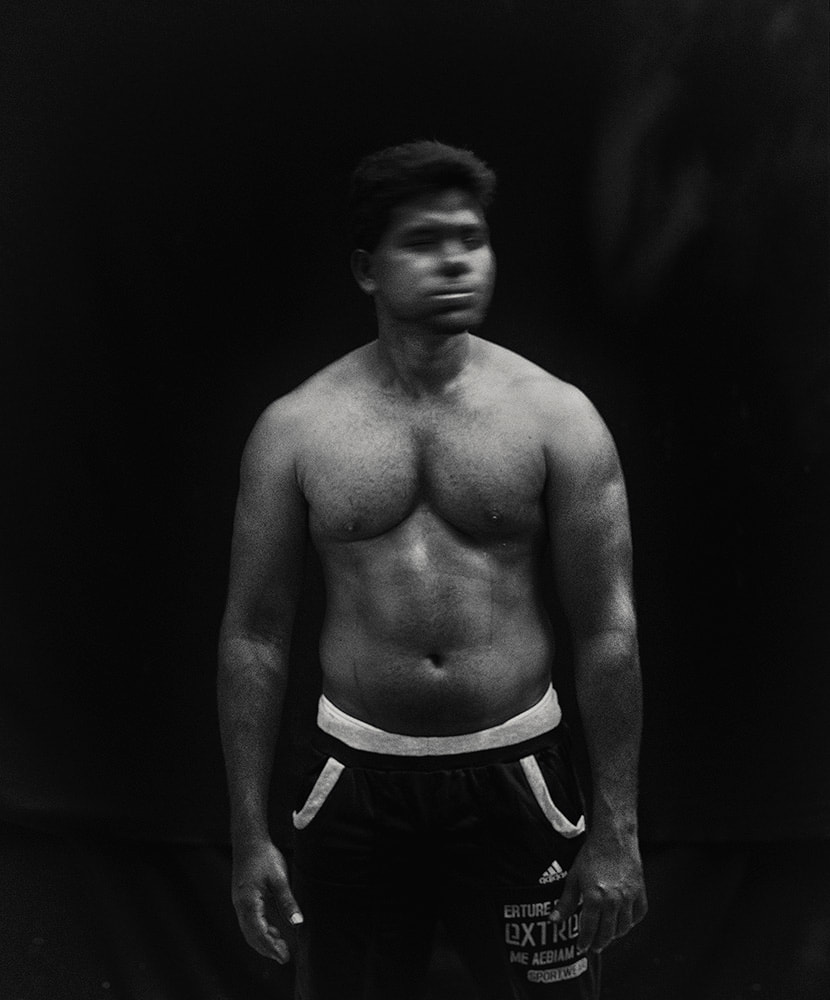

Hoda Afshar, Portrait of Thanus, from the series Remain, 2018 Archival inkjet print, 100 x 83cm (right)

Hoda Afshar, Portrait of Thanus, from the series Remain, 2018 Archival inkjet print, 100 x 83cm (right)

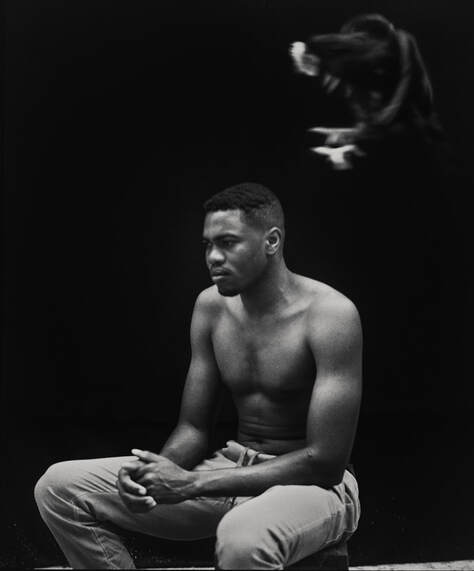

Hoda Afshar, Portrait of Mohamed, from the series Remain, 2018 Archival inkjet print, 100 x 83cm

Hoda Afshar (VIC)

Working across photography and moving-image, Melbourne based Iranian-Australian artist Hoda Afshar explores the nature and possibilities of documentary image-making, and the representation of gender, marginality and displacement.

In the portraiture series Remain, Afshar addresses Australia’s contentious border protection policy and the human rights of asylum seekers. Afshar travelled to Manus Island, an immigration detention facility in Papua New Guinea, to create Remain in collaboration with several stateless men who remained on the island despite the centre’s closure in October 2017. Remain delivers a powerful depiction of the men not as refugees, but as human beings. Featured among the images is Kurdish Iranian journalist and writer Behrouz Boochani, who worked with Afshar as a guide and an artistic collaborator. Remain involved these men retelling their stories, the resulting images bearing witness to life in the camps: from the death of friends and dreams of freedom, to the strange air of beauty, boredom, and violence.

Working across photography and moving-image, Melbourne based Iranian-Australian artist Hoda Afshar explores the nature and possibilities of documentary image-making, and the representation of gender, marginality and displacement.

In the portraiture series Remain, Afshar addresses Australia’s contentious border protection policy and the human rights of asylum seekers. Afshar travelled to Manus Island, an immigration detention facility in Papua New Guinea, to create Remain in collaboration with several stateless men who remained on the island despite the centre’s closure in October 2017. Remain delivers a powerful depiction of the men not as refugees, but as human beings. Featured among the images is Kurdish Iranian journalist and writer Behrouz Boochani, who worked with Afshar as a guide and an artistic collaborator. Remain involved these men retelling their stories, the resulting images bearing witness to life in the camps: from the death of friends and dreams of freedom, to the strange air of beauty, boredom, and violence.

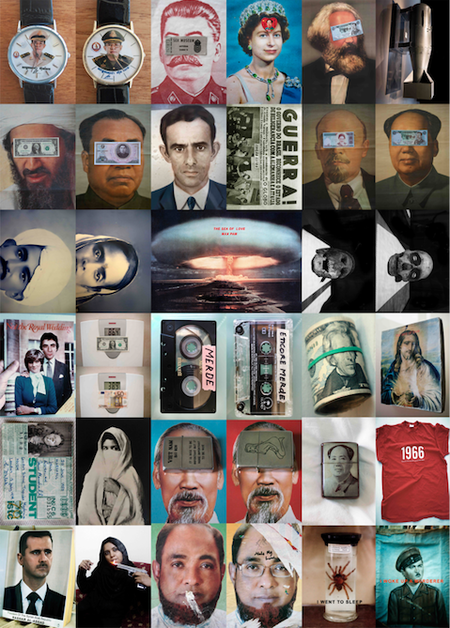

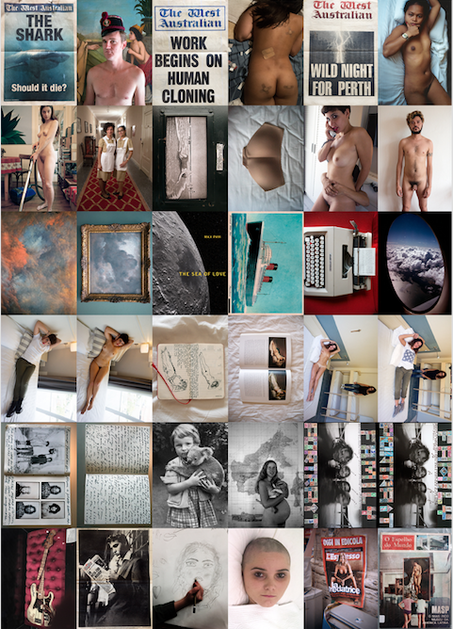

Max Pam, The Sea of Love, 2020 Inkjet photo-rag smooth prints, 18 prints 20 x 40cm each ensemble

Max Pam (WA)

For 50 years Perth based Max Pam has been interpreting his experience through a unique mix of photography and autobiography. Pam combines an interest in a certain kind of representation – the snapshot and the pseudo-documentary ‘decisive moment’ – with other modes of documentation such as images of small mementos, drawings and written diaristic accounts. A distinguishing feature of his work is a constant sensitivity to the face-to-face encounter.

The Sea of Love is a semi-autobiographical sampling of the cultures Pam has lived in over the decades to interrogate the human condition, desire, family, territorial peculiarity and otherness. Presented as an expanded selection of Pam’s latest book, The Sea of Love explores love and obsession in all its forms from the caprices of the popular despot to Pam’s own deeply personal response to desire, family, connection and otherness. The Sea of Love is divided into two ensembles, one personal reflecting Pam’s love obsession with Francisco da Goya’s La Maja, and the other political, reflecting the apparatus of propaganda and populist worship.

For 50 years Perth based Max Pam has been interpreting his experience through a unique mix of photography and autobiography. Pam combines an interest in a certain kind of representation – the snapshot and the pseudo-documentary ‘decisive moment’ – with other modes of documentation such as images of small mementos, drawings and written diaristic accounts. A distinguishing feature of his work is a constant sensitivity to the face-to-face encounter.

The Sea of Love is a semi-autobiographical sampling of the cultures Pam has lived in over the decades to interrogate the human condition, desire, family, territorial peculiarity and otherness. Presented as an expanded selection of Pam’s latest book, The Sea of Love explores love and obsession in all its forms from the caprices of the popular despot to Pam’s own deeply personal response to desire, family, connection and otherness. The Sea of Love is divided into two ensembles, one personal reflecting Pam’s love obsession with Francisco da Goya’s La Maja, and the other political, reflecting the apparatus of propaganda and populist worship.

Angela Tiatia, Metamorphoses of Narcissus I, II, & III, 2019 Pigment print on cotton rag, 80 x 58cm each

Angela Tiatia (NZ/NSW)

Sydney based Angela Tiatia explores contemporary culture, drawing attention to its relationship to representation, gender, neo-colonialism and the commodification of the body and place, often through the lenses of history and popular culture.

This trilogy references literary and artistic sources of the ancient Greek mythological figure Narcissus, a cautionary tale of a young man who fell in love with his own image reflected in a pool of water. Metamorphoses of Narcissus presents a cast of 40 self-worshipping figures involved in individual acts of love and ritual together in a shared portrait of humankind’s interest in survival of the self. A reflection of global selfie culture, this body of work is a comment on the power of social media to influence our perspectives and interactions with the broader world.

Angela Tiatia (NZ/NSW)

Sydney based Angela Tiatia explores contemporary culture, drawing attention to its relationship to representation, gender, neo-colonialism and the commodification of the body and place, often through the lenses of history and popular culture.

This trilogy references literary and artistic sources of the ancient Greek mythological figure Narcissus, a cautionary tale of a young man who fell in love with his own image reflected in a pool of water. Metamorphoses of Narcissus presents a cast of 40 self-worshipping figures involved in individual acts of love and ritual together in a shared portrait of humankind’s interest in survival of the self. A reflection of global selfie culture, this body of work is a comment on the power of social media to influence our perspectives and interactions with the broader world.

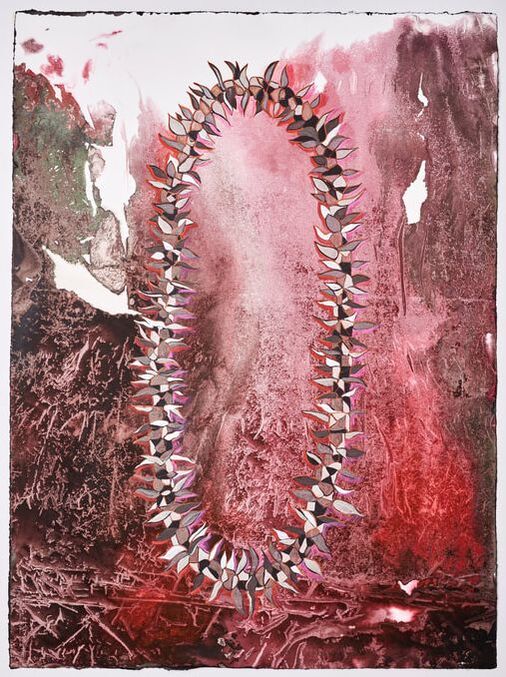

Helen Britton, Australian Welcome, 2020 Tusch and acrylic on paper, 105 x 78cm (top)

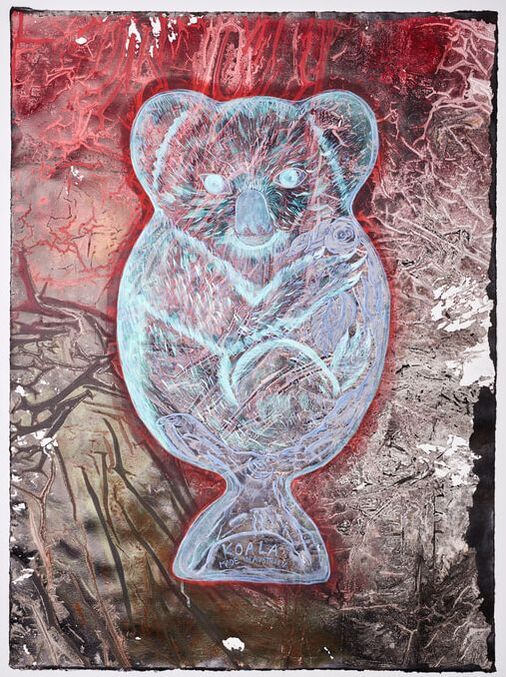

Helen Britton, The Ghost of Innocence, 2020 Tusch and acrylic on paper, 105 x 78cm (bottom)

Helen Britton, The Sad Reminder, 2020 Steel, coal, plastic, paint, 80 x 20 x 50cm (right)

Helen Britton, "Grief” Ring, 2020 Hand carved onyx, silver, 4.5 x 1.3 x 0.6cm (left)

Helen Britton, “Grief” Brooch, 2020 Hand carved onyx, silver, 9 x 6 x 1.3cm (middle)

Helen Britton, “Grief” Ring, 2020 Hand carved onyx, silver, 3.7 x 1.5 x 0.6cm (right)

Helen Britton (GER/WA)

Originally from Australia, the now Munich-based Helen Britton has developed a multidisciplinary practice informed by popular culture, folk art, and the Australian environment. Britton’s recent work reflects on the artist’s personal experiences of Australia’s catastrophic bushfires of 2019-20, and the consequences of endemic ignorance towards Indigenous cultural practices that now play themselves out in massive fires.

Britton speaks of driving down blackened highways, past melted signs, to beaches covered in ash. Black leaves falling from the sky, caught up in the winds fanning the bushfires. By the time Britton carved the first leaves in stone in her “Grief” series, the worst had yet to come. By the New Year the fires were so extreme they were front-lining newspapers internationally. Back in Munich, Britton found her childhood koala hot water bottle, using it as the basis for a screen print to raise money for injured wildlife and as the figure in The Ghost of Innocence.

In the middle of the crisis, the Australian Prime Minister went on holiday to Hawaii. Britton drew on a lei given to her by friends in New Zealand to create Australian Welcome and The Sad Reminder, her response to an ever-deepening anxiety about the direction Australia is sliding.

Helen Britton, “Grief” Brooch, 2020 Hand carved onyx, silver, 9 x 6 x 1.3cm (middle)

Helen Britton, “Grief” Ring, 2020 Hand carved onyx, silver, 3.7 x 1.5 x 0.6cm (right)

Helen Britton (GER/WA)

Originally from Australia, the now Munich-based Helen Britton has developed a multidisciplinary practice informed by popular culture, folk art, and the Australian environment. Britton’s recent work reflects on the artist’s personal experiences of Australia’s catastrophic bushfires of 2019-20, and the consequences of endemic ignorance towards Indigenous cultural practices that now play themselves out in massive fires.

Britton speaks of driving down blackened highways, past melted signs, to beaches covered in ash. Black leaves falling from the sky, caught up in the winds fanning the bushfires. By the time Britton carved the first leaves in stone in her “Grief” series, the worst had yet to come. By the New Year the fires were so extreme they were front-lining newspapers internationally. Back in Munich, Britton found her childhood koala hot water bottle, using it as the basis for a screen print to raise money for injured wildlife and as the figure in The Ghost of Innocence.

In the middle of the crisis, the Australian Prime Minister went on holiday to Hawaii. Britton drew on a lei given to her by friends in New Zealand to create Australian Welcome and The Sad Reminder, her response to an ever-deepening anxiety about the direction Australia is sliding.

Valerie Sparks, Protea, from the series Sanctuary, 2019 Inkjet print wallpaper panel, 200 x 89cm (left)

Valerie Sparks, Grevillea, from the series Sanctuary, 2019 Inkjet print wallpaper panel, 200 x 89cm (middle)

Valerie Sparks, Luculia, from the series Sanctuary, 2019 Inkjet print wallpaper panel, 200 x 89cm (right)

Valerie Sparks, Grevillea, from the series Sanctuary, 2019 Inkjet print wallpaper panel, 200 x 89cm (middle)

Valerie Sparks, Luculia, from the series Sanctuary, 2019 Inkjet print wallpaper panel, 200 x 89cm (right)

Valerie Sparks, Chrysanthemum, from the series Sanctuary, 2019 Inkjet print wallpaper panel, 200 x 89cm (left)

Valerie Sparks, Waratah, from the series Sanctuary, 2019 Inkjet print wallpaper panel, 200 x 89cm (middle)

Valerie Sparks, Andromeda, from the series Sanctuary, 2019 Inkjet print wallpaper panel, 200 x 89cm (right)

Valerie Sparks (VIC)

Melbourne based Valerie Sparks has developed a unique photographic practice responding to the history and aesthetics of immersive environments, from frescos, stereoscopic photographs, and nineteenth century French scenic wallpapers, to contemporary 3D light-based installations and Virtual Reality spaces.

Sparks’ Sanctuary series refers to the idea of a sanctuary as both a nurturing place of refuge for humans, and a place of protection for plants. Interested in the parallels between science and art, Sparks studied the intricate details of introduced and native Australian flora during a residency with Melbourne florist Flowers Vasette to make these photographic wallpapers. Inspired by the achievements of pioneering female botanical artists, Sparks’ works help preserve and remember their contribution to Australia’s biodiversity. Set against a background of stormy skies, the works have a hyperreal and slightly threatening aura that questions the comfortable boundaries of inside and outside and asks who or what is kept out.

Valerie Sparks, Waratah, from the series Sanctuary, 2019 Inkjet print wallpaper panel, 200 x 89cm (middle)

Valerie Sparks, Andromeda, from the series Sanctuary, 2019 Inkjet print wallpaper panel, 200 x 89cm (right)

Valerie Sparks (VIC)

Melbourne based Valerie Sparks has developed a unique photographic practice responding to the history and aesthetics of immersive environments, from frescos, stereoscopic photographs, and nineteenth century French scenic wallpapers, to contemporary 3D light-based installations and Virtual Reality spaces.

Sparks’ Sanctuary series refers to the idea of a sanctuary as both a nurturing place of refuge for humans, and a place of protection for plants. Interested in the parallels between science and art, Sparks studied the intricate details of introduced and native Australian flora during a residency with Melbourne florist Flowers Vasette to make these photographic wallpapers. Inspired by the achievements of pioneering female botanical artists, Sparks’ works help preserve and remember their contribution to Australia’s biodiversity. Set against a background of stormy skies, the works have a hyperreal and slightly threatening aura that questions the comfortable boundaries of inside and outside and asks who or what is kept out.

Ian Williams, Hard Jelly, 2020 Oil on canvas, 120 x 180cm

Ian Williams, Plastic Banquet, 2020 Oil on canvas, 120 x 180cm

Ian Williams, Antimatter, 2020 Oil on canvas, 120 x 180cm

Ian Williams (WA)

Ian Williams’ practice is concerned with the interpretation of reality within virtual environments and how this can be expressed through painting. Using found objects from video games, this Perth based artist utilises the conventions of still life painting to explore the properties of the virtual everyday object.

Playing with the genre of still life, which typically presents inanimate subject matter, these three works originate from the moving digital world. Selecting and exporting everyday objects from within video game environments, Williams creates painting compositions that toy with real world phenomena such as gravity, scale, and the forces of collision. Illuminated from a first person perspective the viewer is placed within a vaguely familiar yet physically impossible choreography of objects.

Ian Williams (WA)

Ian Williams’ practice is concerned with the interpretation of reality within virtual environments and how this can be expressed through painting. Using found objects from video games, this Perth based artist utilises the conventions of still life painting to explore the properties of the virtual everyday object.

Playing with the genre of still life, which typically presents inanimate subject matter, these three works originate from the moving digital world. Selecting and exporting everyday objects from within video game environments, Williams creates painting compositions that toy with real world phenomena such as gravity, scale, and the forces of collision. Illuminated from a first person perspective the viewer is placed within a vaguely familiar yet physically impossible choreography of objects.

James Walker, Precipice, 2013 Acrylic on canvas, 96 x 120.5cm (left)

James Walker, Western Junction: A Winter Approach, 2016 Acrylic on canvas, 105 x 160cm (middle)

James Walker, Midlands: After Flight, 2020 Acrylic on canvas, 92 x 92cm (right)

James Walker, Western Junction: A Winter Approach, 2016 Acrylic on canvas, 105 x 160cm (middle)

James Walker, Midlands: After Flight, 2020 Acrylic on canvas, 92 x 92cm (right)

James Walker, Ellipsism, 2016 Acrylic on wood, 79 x 120cm

James Walker (WA)

In 2018 James Walker relocated to Perth from Launceston where he was an art teacher and an active member of

the Tasmanian arts community. Connection to place and the traces of memory are key themes within his practice based on a childhood obsession with WWII aircraft, the connection and interests he shares with his father, and the dislocation of existing between two places. There is an overarching melancholy to his practice characterised by his work Ellipsism which describes the sadness of knowing that you will not live to see how history turns out.

The focus of Precipice, Western Junction: A Winter Approach and Midlands: After Flight is the sky above Tasmania, and the artist and his father’s shared passion for aircraft. In Western Junction: A Winter Approach Walker recounts his memory of flying radio-controlled aircraft with his father when he was seven. The flying field was full of sensory experiences; vibrations, smells and sounds. His father would time their drive home to coincide with aircraft approaching Launceston airport, stopping to feel them pass low overhead. In his most recent painting, Midlands: After Flight, Walker revisits old memories through photo documentation taken by his father of shared journeys to the model aircraft flying field. The navigation symbols, colour and shapes are a visual memory of the space the artist occupied with his father.

James Walker (WA)

In 2018 James Walker relocated to Perth from Launceston where he was an art teacher and an active member of

the Tasmanian arts community. Connection to place and the traces of memory are key themes within his practice based on a childhood obsession with WWII aircraft, the connection and interests he shares with his father, and the dislocation of existing between two places. There is an overarching melancholy to his practice characterised by his work Ellipsism which describes the sadness of knowing that you will not live to see how history turns out.

The focus of Precipice, Western Junction: A Winter Approach and Midlands: After Flight is the sky above Tasmania, and the artist and his father’s shared passion for aircraft. In Western Junction: A Winter Approach Walker recounts his memory of flying radio-controlled aircraft with his father when he was seven. The flying field was full of sensory experiences; vibrations, smells and sounds. His father would time their drive home to coincide with aircraft approaching Launceston airport, stopping to feel them pass low overhead. In his most recent painting, Midlands: After Flight, Walker revisits old memories through photo documentation taken by his father of shared journeys to the model aircraft flying field. The navigation symbols, colour and shapes are a visual memory of the space the artist occupied with his father.

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, Vantage, 2019 Oil on plywood, 120 x 106cm (right)

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, The Green Cover, 2020 Oil on plywood, 30 x 30cm (left)

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, The Modernist Gem, 2020 Oil on plywood, 30 x 30cm (middle)

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, The Interloper, 2020 Oil on plywood, 30 x 30cm (right)

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, The Modernist Gem, 2020 Oil on plywood, 30 x 30cm (middle)

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, The Interloper, 2020 Oil on plywood, 30 x 30cm (right)

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, Mujarr (Australian Christmas Tree), 2020 Oil on plywood, 60 x 60cm (left)

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, Institutional Jungle, 2020 Oil on plywood, 60 x 60cm (right)

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, Institutional Jungle, 2020 Oil on plywood, 60 x 60cm (right)

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, The Project, 2020 Oil on plywood, 30 x 30cm

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter, Skip Paradise, 2019 Oil on canvas, 120 x 154cm

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter (WA)

The extensive individual exhibition and education histories of married Western Australian artists Bruce and Nicole Slatter overlapped into a joint painting practice in 2016. Sharing the formative experience of a 1970s suburban upbringing in Perth’s northern suburbs, their work can be seen as a visual record of a conversation between two local sightseers about the objects and surroundings that define an Australian suburban identity.

Offering a view into seemingly mundane scenarios of suburban life their jointly painted work is imbued with a sense of the uncanny characteristic of the Australian Gothic, a literary and artistic genre concerned with mystery and the relationship between the natural landscape, colonial architecture and history. Rendered with disarming realism, Vantage and The Green Cover set scenes that appear recently vacated, while The Project, Skip Paradise and The Interloper present the abandoned dreams of urban ideals. The Slatters find a hopeful beauty in the cycles of aspiration and entropy within dilapidated and forgotten corners of suburbia.

Bruce Slatter and Nicole Slatter (WA)

The extensive individual exhibition and education histories of married Western Australian artists Bruce and Nicole Slatter overlapped into a joint painting practice in 2016. Sharing the formative experience of a 1970s suburban upbringing in Perth’s northern suburbs, their work can be seen as a visual record of a conversation between two local sightseers about the objects and surroundings that define an Australian suburban identity.

Offering a view into seemingly mundane scenarios of suburban life their jointly painted work is imbued with a sense of the uncanny characteristic of the Australian Gothic, a literary and artistic genre concerned with mystery and the relationship between the natural landscape, colonial architecture and history. Rendered with disarming realism, Vantage and The Green Cover set scenes that appear recently vacated, while The Project, Skip Paradise and The Interloper present the abandoned dreams of urban ideals. The Slatters find a hopeful beauty in the cycles of aspiration and entropy within dilapidated and forgotten corners of suburbia.

Karrabing Film Collective, Mermaids, Mirror Worlds, 2018 Two-channel video, 34 mins 50 seconds

Karrabing Film Collective (NT)

The Karrabing Film Collective is an intergenerational group of around thirty artists and filmmakers, most of whom

are indigenous to the Northern Territory of Australia. Shot using iPhones, Karrabing’s films dramatise the daily experiences of its members and their various interactions with corporate and state entities, interweaving personal scenarios with Dreaming stories, alternative histories, and speculative futures.

The dual screen installation Mermaids, Mirror Worlds features promotional material from industrial giants such as Monsanto and the Dow Chemical Corporation alongside a fictional story set in a toxic ravaged world. The latter centres on a young Indigenous man, Aiden, who was captured as a baby to be a part of a medical experiment to save white people, and his release outside to his family.

In this fictional world, white people must protect themselves by remaining indoors – only Indigenous people can survive outside in a world poisoned by capitalism. Mermaids, Mirror Worlds weaves a dystopic and jarring narrative that mirrors the challenges faced by Karrabing members and their communities in relation to government regulation, corporate and industrial interests, and the natural environment.

Karrabing would like to pay respect to our ancestors, who passed down the stories about our country and taught

us to keep them strong in our hearts and practices. They have left us, but they remain with us ever stronger.

Karrabing Film Collective (NT)

The Karrabing Film Collective is an intergenerational group of around thirty artists and filmmakers, most of whom

are indigenous to the Northern Territory of Australia. Shot using iPhones, Karrabing’s films dramatise the daily experiences of its members and their various interactions with corporate and state entities, interweaving personal scenarios with Dreaming stories, alternative histories, and speculative futures.

The dual screen installation Mermaids, Mirror Worlds features promotional material from industrial giants such as Monsanto and the Dow Chemical Corporation alongside a fictional story set in a toxic ravaged world. The latter centres on a young Indigenous man, Aiden, who was captured as a baby to be a part of a medical experiment to save white people, and his release outside to his family.

In this fictional world, white people must protect themselves by remaining indoors – only Indigenous people can survive outside in a world poisoned by capitalism. Mermaids, Mirror Worlds weaves a dystopic and jarring narrative that mirrors the challenges faced by Karrabing members and their communities in relation to government regulation, corporate and industrial interests, and the natural environment.

Karrabing would like to pay respect to our ancestors, who passed down the stories about our country and taught

us to keep them strong in our hearts and practices. They have left us, but they remain with us ever stronger.

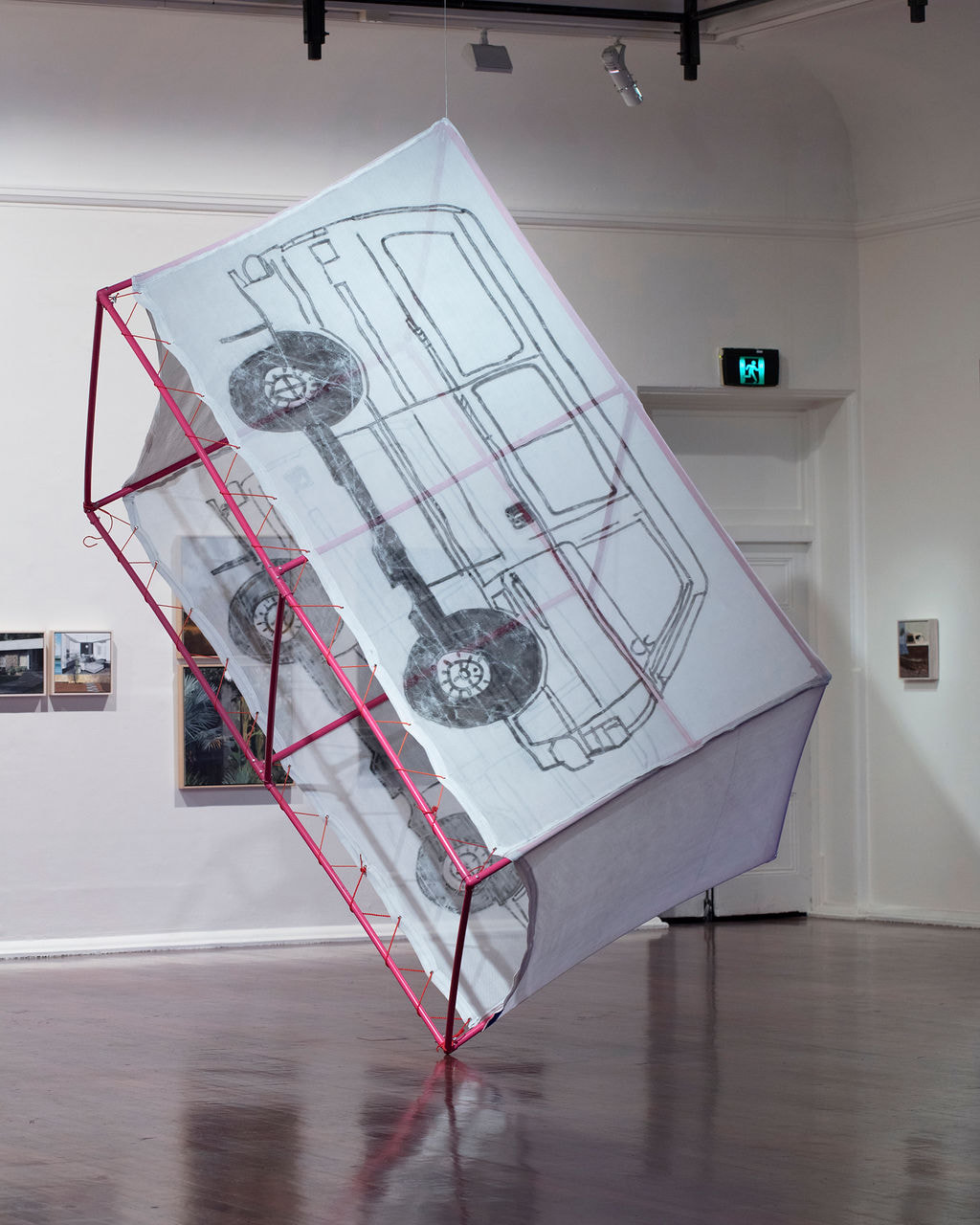

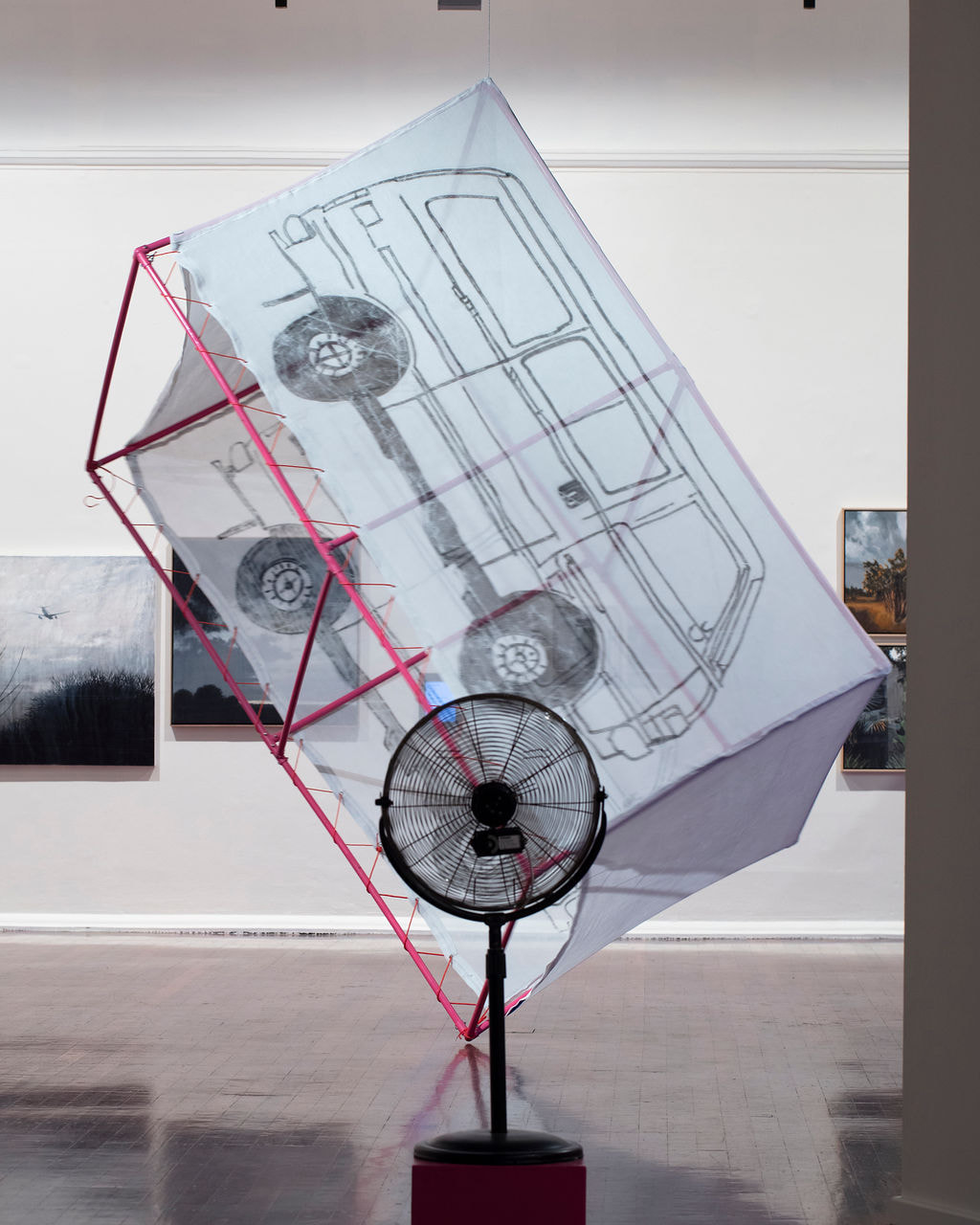

Bruno Booth, New fossil, same molecules, 2020 Polyurethane, enamel, steel, rope, thread, electronics, PIR sensor and fan, 274 x 150 x 150cm

Bruno Booth, And puddles, 2020, HD video with sound. Open captioned 4 mins

Bruno Booth, Burnt out but still fading in, 2020 Oil and acrylic polymer paint on canvas, 65 x 40cm (left)

Bruno Booth, High carb, low effort, 2020 Steel, fleece, silk, embroidery and acrylic polymer paint, 49 x 72cm (right)

Bruno Booth (WA)

Bruno Booth is an emerging Fremantle-based artist with a physical disability, working across the mediums of painting, social engagement, sculpture, video and installation. Booth’s new work is inspired by the under-representation of disabled people in popular culture, and the navigational challenges that he himself faces as a wheelchair user.

Somewhat of a self portrait, And puddles is part poem, part music video that serves as a disjointed and surreal narrative of what it means to be seen as disabled.

Booth describes disability as ‘not sexy’, the word conjuring up images of hospitals, concessions made and what could have been. Growing up in the 1990s disability was absent from media outside of the Paralympics and occasional human interest stories. The closest thing Booth had to role models that looked like him were cartoon characters. The mutants and misfits in these animated worlds had superpowers and were loved not in spite of their differences but because of them. Burnt out but still fading in responds to arguments that we have progressed into more nuanced understandings of what it means to have a disability, with the rebuttal that until we do away with the categorisation, those associations of pity, fear and unease will remain.

In New fossil, same molecules Booth reimagines an old BMC (British Medical Council) ambulance that his father converted into a campervan when he was a child. Almost every summer his family would drive from their home in Lancashire in the North West of England down to Devon, where they would spend two to three weeks camping, using the converted ambulance as a base. The idea of renewal and rebirth, of repurposing old materials, made a lasting impression on Booth, who remembers with amazement how his father turned the van into a cosy home for four. While memories of these trips have inevitably faded and blurred with the passing of time, there remains a connection, a window Booth can re-open into his childhood.

Booth cites cats as strong ‘influencers’ on his practice. Slinking through the gallery in a high gloss Adidas tracksuit is the enigmatic High carb, low effort, a wry comment on the paradox of acquisition and consumption. While today we find ourselves with more wealth, more possessions and more social capital than ever before, a steady stream of influencers espouse the virtues of a stripped-down existence, minimal lives furnished with only the most stylish essentials. Is minimalism a cure for capitalist overindulgence, or simply a new mode of consumption, an excess of less? Which path do we choose?

Bruno Booth, High carb, low effort, 2020 Steel, fleece, silk, embroidery and acrylic polymer paint, 49 x 72cm (right)

Bruno Booth (WA)

Bruno Booth is an emerging Fremantle-based artist with a physical disability, working across the mediums of painting, social engagement, sculpture, video and installation. Booth’s new work is inspired by the under-representation of disabled people in popular culture, and the navigational challenges that he himself faces as a wheelchair user.

Somewhat of a self portrait, And puddles is part poem, part music video that serves as a disjointed and surreal narrative of what it means to be seen as disabled.

Booth describes disability as ‘not sexy’, the word conjuring up images of hospitals, concessions made and what could have been. Growing up in the 1990s disability was absent from media outside of the Paralympics and occasional human interest stories. The closest thing Booth had to role models that looked like him were cartoon characters. The mutants and misfits in these animated worlds had superpowers and were loved not in spite of their differences but because of them. Burnt out but still fading in responds to arguments that we have progressed into more nuanced understandings of what it means to have a disability, with the rebuttal that until we do away with the categorisation, those associations of pity, fear and unease will remain.

In New fossil, same molecules Booth reimagines an old BMC (British Medical Council) ambulance that his father converted into a campervan when he was a child. Almost every summer his family would drive from their home in Lancashire in the North West of England down to Devon, where they would spend two to three weeks camping, using the converted ambulance as a base. The idea of renewal and rebirth, of repurposing old materials, made a lasting impression on Booth, who remembers with amazement how his father turned the van into a cosy home for four. While memories of these trips have inevitably faded and blurred with the passing of time, there remains a connection, a window Booth can re-open into his childhood.

Booth cites cats as strong ‘influencers’ on his practice. Slinking through the gallery in a high gloss Adidas tracksuit is the enigmatic High carb, low effort, a wry comment on the paradox of acquisition and consumption. While today we find ourselves with more wealth, more possessions and more social capital than ever before, a steady stream of influencers espouse the virtues of a stripped-down existence, minimal lives furnished with only the most stylish essentials. Is minimalism a cure for capitalist overindulgence, or simply a new mode of consumption, an excess of less? Which path do we choose?

Photography: Bo Wong, Images courtesy the artists.